stdClass Object

(

[id] => 18701

[title] => The fracture of the ora et labora generated two different forms of individualism

[alias] => the-fracture-of-the-ora-et-labora-generated-two-different-forms-of-individualism

[introtext] => The market and the temple/20 - In a few decades, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation consumed the ethical ground conquered by the merchants between the 14th century and 16th century.

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 21/03/2020

The 17th century was more "religious" than the 14th century, but perhaps not necessarily more "Christian". And after the friendship between friars and merchants, a distant suspicion began to re-emerge between clerics and entrepreneurs.

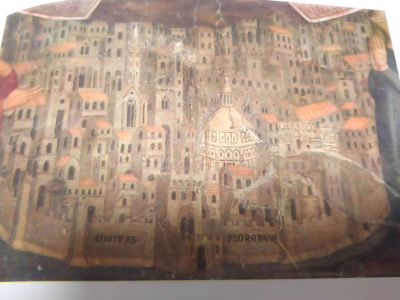

With the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, the ethical ground that the Italian and European merchants had conquered between the 13th and 16th centuries disappeared in a few decades. The economic ethics of the Counter-Reformation returned to that of four centuries earlier, as if Olivi, Duns Scotus, Boccaccio, Francesco Datini and Benedetto Cotrugli had ver written or worked at all; as if the miracles of beauty and civilization of Florence, Genoa and Venice had been erased from the collective consciousness. The virtues to be praised were once again the aristocratic, noble and agricultural ones of the past, and no longer those of the market. The great clock telling the time of history was turned back to the feudal society of the eleventh century. The encyclical Vix pervenit of Benedict XIV in 1745, which declared the interest on mortgages legitimate, presented the exact same theses put forth by the Franciscans but almost half a millennium later. The medieval pages of economic ethics of the Franciscan Bernardino of Siena or of the Dominican Antonino of Florence are still studied and meditated on today; on the other hand, no one remembers the homilies of Geronimo Garimberto or the Lenten days of Paolo Segneri, the great economic moralists of the age of Counter-Reformation. The 17th century, with its Baroque explosion of devotion, was more religious than the 14th century, but perhaps not necessarily more Christian.

[fulltext] => The most important economic and civil effects of the Counter-Reformation were the unforeseen and collateral ones. The first one is the one that is best known. The fight against usury became a hot topic again. Any contract could be seen as implicitly usurious. Dealing with economics and trade therefore became a dangerous profession; better to devote oneself to the liberal professions and above all to agriculture, since the attitude of the Church was much softer on agricultural income and usury (the "censuses"). Hence, the progressive distance that was created between the merchant class and the Catholic Church. Something similar to what was happening with theology happened with trading: since dealing with theology could be risky and even lead to the stake in the shadow of the Alps, after the Reformation Italian and Latin scholars began to devote themselves to other things (music, art, literature and theater), and modern theology became a predominantly Protestant affair. To get an idea of the situation, just take a look at the most popular Handbook for confessors by Abbot Gaume and its very long list of special cases to be carefully checked during confession (1852, p.163). Anyone who knows entrepreneurs knows very well that if there is something that this category of people detests, it is external interference in the choices of the "internal forum" of their companies. Hence, better to entrust the ordinary practice of the sacraments to one’s wife or sisters, and thus avoid penance, excommunication, infamy or even dishonour.

The conquered autonomy of earthly things was gradually reabsorbed by a new clericalization of life and people’s conscience in general. In the late Middle Ages, the Franciscan and Dominican friars were in charge of watching over the ethical vigilance of the merchants. This was done within the frames of an ordinary acquaintance and friendship, and was a participatory and supportive accompaniment of people of flesh and blood observed in the squares, not imagined inside confessionals. The trauma of the Reformation-Counter-Reformation devoured this heritage of trust and confidence, and re-created the mutual suspicion and general distance typical of the first Christian millennium.

The role played by the religious orders is another important indirect effect of the Counter-Reformation. The climate created by the Reformation generated a general suspicion towards the ancient religious orders (Luther was an Augustinian monk) in the Catholic world. From being considered virtual cradles of spirituality and culture monasteries and convents, especially the male ones, began to be looked upon as potential dens of heretics, because the monks and friars were scholars of Scripture and from a "charismatic" perspective open to the winds of reform. A fair number of monks and friars were investigated and subsequently condemned. Some Franciscans, for example, accused of Lutheranism were executed around the middle of the sixteenth century: Giovanni Buzio, Bartolomeo Fanzio, Girolamo Galateo, Cornelio Giancarlo and Baldo Lupatino. The Tridentine Reform was not based on the ancient orders (monks and Mendicants), but on the new orders, in particular the Jesuits, but also the Barnabites, the Theatines, the Somascans, the Capuchins and the diocesan priests. The new suspicion and disdain towards the ancient monks not only held back the development of those economic, cultural and technological laboratories that the monasteries had been for many centuries; it also greatly complicated the economic and social action of the Franciscans and their pastoral care of merchants and artisans within the cities. The development that the Monti di Pietà had experienced thanks to the action of the Friars Minor, went through a crisis from the second half of the 16th century. The Monti, which continued to be founded, gradually separated from the Franciscans to become municipal institutions or dioceses. Thus, they lost their nature as banks that also supported the activity of small and medium-sized entrepreneurs to transform into mere organizations of assistance and charity: «The Council of Trent placed the Monte di Pietà between the Pious Institutes and between the places that the bishops were required to visit regularly» (Maria G. Muzzarelli, entry on the "Monti di Pietà in the Dictionary of Civil Economy/ Dizionario di Economia Civile).

A third indirect effect of the Counter-Reformation was the progressive "feminization" of the sacred and of religion: «Men could confess, women had to» (Adriano Prosperi, The tribunals of conscience/ I tribunali della coscienza), because public attendance of the sacraments was a precondition for access to the marriage market and for the public honour of married couples. The economic and political sphere was increasingly understood as a male affair, while sacred and religious practices became the realm of women, married or nuns - "home and church". Religious practices and virility were a complicated combination and an increasingly feminine popular piety produced devotional practices where males felt uncomfortable and therefore deserted - this process self-nurtured itself in churches furnished by (and for) female sensibility, with related language, prayers and songs, a femininity that was not felt in the Protestant churches. The practice of the Catholic religion began to become a "profession" of women governed entirely by males. Armies with female soldiers and male officers. Women also became the main entrance for the Church into the life of families and therefore society: «Men are naturally pagan and it is up to the Christian wives not so much to convert him as to save his soul. The wild male drinks, plays, blasphemes, harasses women, fights with his hands; the missionary bride does not contradict these customs of his, but pays attention what is essential, that is the minimum number of Masses, sacraments and devotions that are sufficient to remain fundamentally at peace with heaven. At that point, all that remains to be done is to collect the soul directly on the deathbed» (Luigi Meneghello, Libera nos a malo). The theology of vicarious suffering, then, worked perfectly in this oikonomia of the family: women could save their husbands, fathers and children by offering their penances and sacrifices.

Confession also served the side of "demand" well: women, especially consecrated women, found the only contact with the outside world and with males in their priests, which often evolved into friendship and confidence. So much so, that the management of the confessionals, which spread during the Counter-Reformation was particularly accurate and disciplined, in part due to the repeated crimes of sollecitatio and solicitation in the confessionals, and the many conflicts between nuns. Like those reported in Ferrara in 1623, when a «confessor, showing concern for only a dozen young nuns, had created a rift among the nuns: most of them, out of spite, had abstained from practicing the sacrament for months» (Mario Sanseverino, A dangerous ministry: confessing nuns in the city of Naples of the Counter-Reformation 1563-1700/ Un pericoloso ministero: confessare le monache nella Napoli della Controriforma 1563-1700). This is why after the Council of Trent, the practice of a single confessor for an entire monastery was introduced and Pope Gregory XIII introduced the limit of three years of mandate.

It is interesting to note that while at the beginning of the application of the three-year rule it was the nuns who asked for the rotation to be respected, a few decades later the attitude had changed and many nuns asked for an extension of the three-year period. It is not surprising then that, in order to avoid the trade in gifts and tips between individual nuns and confessors, confessors began to be paid in various cities towards the end of the 16th century. A further intersection between economy and religion: the payment of a fair monetary wage (for example, the salary was 60 ducats at the monastery of Santa Croce in Lucca) used as a tool to discourage the creation of relational goods for an inappropriate or at least imprudent use. The common good of the monastery (or at least what was perceived as such by the leaders, but perhaps not so by the nuns) was pursued with the introduction of public money instead of private gifts. Telling us that money almost always drives out and replaces gifts, but the evaluation that the effects of this replacement has on all parties involved is not that obvious - even clientelist systems and mafia organizations are defeated with the introduction of transparent contracts.

Finally, one last effect concerns the confrontation with Protestant countries. In the world of the Reformation - Max Weber reminds us - the laity essentially became the place of the working profession understood as a vocation (beruf). When the monasteries were closed by Luther and Calvin, the idea developed that the new place in which to cultivate the Christian vocation was civil work: the convent became the city. The Protestants picked up the labora of the monks' ora et labora, which also became a new form of prayer. The Catholic world of the Counter-Reformation also experienced a migration from the monastic world, but they kept the ora, prayer, from the monastic formula, which also became a new form of work, especially for women, within the monasteries or in their homes. In fact, the monastic religious practices (the ideal of perfection, accompaniment, spiritual struggle, penance...) became the ideal of life for the laity, especially for women. Hence, it is not true that individualism is the cipher of Protestantism alone. There was also a Catholic individualism, albeit a very different one. Nordic individualism developed on the basis of rights and freedoms and became the individualism of the external forum. The Latin and Catholic one became an individualism of the internal, private, family and feminine forum, with women employed in the care of the soul and the home, but excluded from the external forum, which remained an exclusive male domain (in Catholic countries more than in Protestant ones).

However, there is good news. The ancient spirit of the art of trading is not dead. The fire stayed alive under the ashes. Even if they are not aware of it, many Italian and Spanish entrepreneurs have the same ethical DNA as the merchants who once made our cities and churches splendid, their very virtues, their same civil love. They are not aware of it, but it is true. A good merchant spirit that is still warm, alive and vivifying.

***

The series of twenty articles dedicated to the origin of mercantile ethics comes to an end today. An exciting journey full of surprises, as has always been the case in many of the series of articles that I have written for "Avvenire", thanks to the courageous trust of its Chief Editor. As of next Sunday, I have agreed to return to my second line of research and passion: biblical commentaries. Together once again, we will begin with the Book of Ruth.

[checked_out] => 0

[checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00

[catid] => 1160

[created] => 2021-03-21 01:35:45

[created_by] => 4501

[created_by_alias] => Luigino Bruni

[state] => 1

[modified] => 2021-04-04 09:11:10

[modified_by] => 609

[modified_by_name] => Super User

[publish_up] => 2021-03-21 01:42:13

[publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00

[images] => {"image_intro":"","image_sp_full":"images\/2021\/03\/21\/210320-la-fiera-e-il-tempio1.png","image_sp_thumb":"images\/2021\/03\/21\/210320-la-fiera-e-il-tempio1_thumbnail.png","image_sp_medium":"images\/2021\/03\/21\/210320-la-fiera-e-il-tempio1_medium.png","image_sp_large":"images\/2021\/03\/21\/210320-la-fiera-e-il-tempio1_large.png","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""}

[urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""}

[attribs] => {"article_layout":"","show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_associations":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_page_title":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":"","spfeatured_image":"images\/2021\/03\/21\/210320-la-fiera-e-il-tempio1.png","spfeatured_image_alt":"","post_format":"standard","gallery":"","audio":"","video":"","helix_ultimate_video":"","helix_ultimate_article_format":"standard","helix_ultimate_image":"images\/2021\/03\/21\/210320-la-fiera-e-il-tempio1.png","link_title":"","link_url":"","quote_text":"","quote_author":"","post_status":""}

[metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""}

[metakey] =>

[metadesc] =>

[access] => 1

[hits] => 2329

[xreference] =>

[featured] => 1

[language] => en-GB

[on_img_default] =>

[readmore] => 11265

[ordering] => 0

[category_title] => EN - The Market and the Temple

[category_route] => oikonomia/it-la-fiera-e-il-tempio

[category_access] => 1

[category_alias] => en-the-market-and-the-temple

[published] => 1

[parents_published] => 1

[lft] => 110

[author] => Luigino Bruni

[author_email] => lourdes.hercules.91@gmail.com

[parent_title] => Oikonomia

[parent_id] => 1025

[parent_route] => oikonomia

[parent_alias] => oikonomia

[rating] => 0

[rating_count] => 0

[alternative_readmore] =>

[layout] =>

[params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object

(

[data:protected] => stdClass Object

(

[article_layout] => _:default

[show_title] => 1

[link_titles] => 1

[show_intro] => 1

[info_block_position] => 0

[info_block_show_title] => 1

[show_category] => 1

[link_category] => 1

[show_parent_category] => 1

[link_parent_category] => 1

[show_associations] => 0

[flags] => 1

[show_author] => 0

[link_author] => 0

[show_create_date] => 1

[show_modify_date] => 0

[show_publish_date] => 1

[show_item_navigation] => 1

[show_vote] => 0

[show_readmore] => 0

[show_readmore_title] => 0

[readmore_limit] => 100

[show_tags] => 1

[show_icons] => 1

[show_print_icon] => 1

[show_email_icon] => 1

[show_hits] => 0

[record_hits] => 1

[show_noauth] => 0

[urls_position] => 1

[captcha] =>

[show_publishing_options] => 1

[show_article_options] => 1

[save_history] => 1

[history_limit] => 10

[show_urls_images_frontend] => 0

[show_urls_images_backend] => 1

[targeta] => 0

[targetb] => 0

[targetc] => 0

[float_intro] => left

[float_fulltext] => left

[category_layout] => _:blog

[show_category_heading_title_text] => 0

[show_category_title] => 0

[show_description] => 0

[show_description_image] => 0

[maxLevel] => 0

[show_empty_categories] => 0

[show_no_articles] => 0

[show_subcat_desc] => 0

[show_cat_num_articles] => 0

[show_cat_tags] => 1

[show_base_description] => 1

[maxLevelcat] => -1

[show_empty_categories_cat] => 0

[show_subcat_desc_cat] => 0

[show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 0

[num_leading_articles] => 0

[num_intro_articles] => 14

[num_columns] => 2

[num_links] => 0

[multi_column_order] => 1

[show_subcategory_content] => -1

[show_pagination_limit] => 1

[filter_field] => hide

[show_headings] => 1

[list_show_date] => 0

[date_format] =>

[list_show_hits] => 1

[list_show_author] => 1

[list_show_votes] => 0

[list_show_ratings] => 0

[orderby_pri] => none

[orderby_sec] => rdate

[order_date] => published

[show_pagination] => 2

[show_pagination_results] => 1

[show_featured] => show

[show_feed_link] => 1

[feed_summary] => 0

[feed_show_readmore] => 0

[sef_advanced] => 1

[sef_ids] => 1

[custom_fields_enable] => 1

[show_page_heading] => 0

[layout_type] => blog

[menu_text] => 1

[menu_show] => 1

[secure] => 0

[helixultimatemenulayout] => {"width":600,"menualign":"right","megamenu":0,"showtitle":1,"faicon":"","customclass":"","dropdown":"right","badge":"","badge_position":"","badge_bg_color":"","badge_text_color":"","layout":[]}

[helixultimate_enable_page_title] => 1

[helixultimate_page_title_alt] => Oikonomia

[helixultimate_page_subtitle] => Sul Confine e Oltre

[helixultimate_page_title_heading] => h2

[page_title] => The Market and the Temple

[page_description] =>

[page_rights] =>

[robots] =>

[access-view] => 1

)

[initialized:protected] => 1

[separator] => .

)

[displayDate] => 2021-03-21 01:35:45

[tags] => Joomla\CMS\Helper\TagsHelper Object

(

[tagsChanged:protected] =>

[replaceTags:protected] =>

[typeAlias] =>

[itemTags] => Array

(

)

)

[slug] => 18701:the-fracture-of-the-ora-et-labora-generated-two-different-forms-of-individualism

[parent_slug] => 1025:oikonomia

[catslug] => 1160:en-the-market-and-the-temple

[event] => stdClass Object

(

[afterDisplayTitle] =>

[beforeDisplayContent] =>

[afterDisplayContent] =>

)

[text] => The market and the temple/20 - In a few decades, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation consumed the ethical ground conquered by the merchants between the 14th century and 16th century.

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 21/03/2020

The 17th century was more "religious" than the 14th century, but perhaps not necessarily more "Christian". And after the friendship between friars and merchants, a distant suspicion began to re-emerge between clerics and entrepreneurs.

With the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, the ethical ground that the Italian and European merchants had conquered between the 13th and 16th centuries disappeared in a few decades. The economic ethics of the Counter-Reformation returned to that of four centuries earlier, as if Olivi, Duns Scotus, Boccaccio, Francesco Datini and Benedetto Cotrugli had ver written or worked at all; as if the miracles of beauty and civilization of Florence, Genoa and Venice had been erased from the collective consciousness. The virtues to be praised were once again the aristocratic, noble and agricultural ones of the past, and no longer those of the market. The great clock telling the time of history was turned back to the feudal society of the eleventh century. The encyclical Vix pervenit of Benedict XIV in 1745, which declared the interest on mortgages legitimate, presented the exact same theses put forth by the Franciscans but almost half a millennium later. The medieval pages of economic ethics of the Franciscan Bernardino of Siena or of the Dominican Antonino of Florence are still studied and meditated on today; on the other hand, no one remembers the homilies of Geronimo Garimberto or the Lenten days of Paolo Segneri, the great economic moralists of the age of Counter-Reformation. The 17th century, with its Baroque explosion of devotion, was more religious than the 14th century, but perhaps not necessarily more Christian.

[jcfields] => Array

(

)

[type] => intro

[oddeven] => item-odd

)