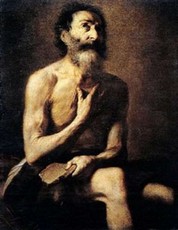

A Man Named Job/13 - Dialogue, even the most unexpected type, helps understand life and God

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 07/06/2015

Guido Ceronetti Il libro di Giobbe (The Book of Job)

Job has ended his speeches. His 'friends' have humiliated and disappointed him, but they also allowed us to find more and more profound reasons for his innocence. In moments of deep discernment on the justice of our life and that of the world, dialogue is an essential tool. We may only manage to understand the deepest questions of our existence and penetrate the darkest depths of our soul in company, by performing a dialogue.

Even when the interlocutors are not our friends, they do not understand us and hurt us, the truth about us emerges in dialogue with other humans, with God and with nature. Instances of solitude are only good when they represent a break between two dialogues. To know who we really are, to reach the furthest and truest corners of our heart above all we need to speak and to listen. In the nights of life it is better not to be well but in company than to be alone.

Job got to the end of his trial with raised head. Like a 'prince' he is waiting for God but he does not know if he will arrive, and if it will be the God of his old 'friends' or a new God. And we, unknowing just like him, share in his wait. The Bible is alive and true as long as it is capable of surprising us. If we can wonder here and now again at the sea opening in front of us while we are chased by the pharaoh's army; if we desperately witness the death of a man on the cross and then we are out of breath when we hear him, alive, pronouncing our name.

The first surprise comes at the end of the Job's words (acting as his own lawyer) is the arrival of a new character: Elihu. It is not clear if it is a character that is expected in the initial script of the play and kept intentionally hidden until this point, a spectator that suddenly bursts onto the scene, or even the theatre director who wants to make his different voice heard. What is certain is that no reader approaching this book for the first time really expects Elihu at this point. He wasn't there in the prologue, and the dramatic tension of the text prepared us to meet only one last character: Elohim. But this book is also great for its twists, the continuing leaps that force us to keep the desire for the words of Elohim alive: we all want these to be great, at least as great as those of Job.

Perhaps an early draft of the book ended with chapter 31, when Job answered all the charges of his interlocutors and silenced them. The silence of all those involved could have been the earliest conclusion of the book. Job had finished the test, and Satan had won his bet. Perhaps there was no need of Elihu, nor the words of Elohim, because - come to think of it - God has already said everything in the prologue of the book. But the great books, certainly the Bible's books, are still alive because, as it happened in ancient cities, the first temples are transformed into churches, the new houses are built using the stones of the old one, new architectural styles are born around the first buildings. The little poem of Elihu is a new square in Job's town, the most recent of the first large forums and temples, artistically less original, and too large not to disturb the harmony of the ancient landscape. A place that we have to cross anyway. Walking through it we will discover some interesting corners, and coming on top of some of its steps we will see new perspectives on the ancient and eternal beauty of this town.

“So these three men ceased to answer Job, because he was righteous in his own eyes. Then Elihu the son of Barachel the Buzite, of the family of Ram, burned with anger. He burned with anger at Job because he justified himself rather than God. He burned with anger also at Job's three friends because they had found no answer, although they had declared Job to be in the wrong.” (32,1-3).

A first interesting thing about Elihu is his name that is very similar to that of the prophet Elijah: “He is my God”. Elihu is the only character in the book with a clear Jewish connotation. Elihu also only has a genealogy: he is from the region of Buz. We know it from Genesis (22,22-24) that two grandsons of Abraham are called Us and Buz, and Us is the region of Job. There are two facts that place Elihu right next to Job and the culture of Israel. Elihu tells us that he wants to put himself on a par of Job, in a dialogue on equal terms between two earthlings: “Behold, I am toward God as you are; I too was pinched off from a piece of clay” (33,6).

The first 31 chapters of the Book of Job are very radical and extreme for any reader in any era. If we are honest, we cannot go into crisis, because this song of the innocent righteous forces us to reconsider our theologies, religions and ideologies deeply. It obliges us to put ourselves on the side of the victims and their questions that take off our mask of idolatry, watching the world from the bottom up, to question God starting from the poor and not vice versa (as is our habit deriving from the same religions). During our reading, when the questions of Job begin to hurt us, the temptation to amend it, to tone down his radical message may be born really easily so as to be more comfortable inside the story. One day, when the text was still in a permeable phase and prior to final editing, a generation of intellectuals perhaps had the courage and the audacity to meddle in that old song of a misfortunate innocent man, and inserted of a long digression in the original text (chs. 32-37) to make it less scandalous a defeat of traditional theology and less clear a victory of Job - and perhaps to improve God's discourses themselves: “Beware lest you say, ‘We have found wisdom; God may vanquish him, not a man.’” (32,13). The authors of Elihu do not accept defeat on the level of dialogic arguments: they want to attempt a last statement and show that there are other all-human reasons to disprive Job's 'blasphemy'.

Yet their result is modest. They find very few new arguments, although some of the verses here are worthy of the best pages of Job (eg. from 33,15-18; 27-29). Elihu's most original thesis - well-known in the traditional wisdom of Israel but almost completely absent in the arguments of Job's three friends - is about the salvific role of suffering that God sends to improve and convert his creatures: “Man is also rebuked with pain on his bed and with continual strife in his bones” (33,19). Here we find an idea that runs through the whole Judeo-Christian universe and is fascinating because it also contains a truth. It is a thesis, however, that poses too many problems in itself and it certainly does not work for Job.

We cannot deny that in the biblical tradition there is a theological line according to which God sends various forms of suffering to mankind for their conversion (it is enough to think of the 'plagues of Egypt'). But when a salvific reading of suffering and pain prevails in religions, there is always the temptation not to do anything to alleviate human suffering and that of the poor. They can also insinuate the idea and practice that it is good to let people in their suffering because if it was alleviated or eliminated the sufferer may lose the chance to save themselves. Job, however, is waiting for another God that is not the cause of human suffering - and we join him in this. He is looking for a face of Elohim who is a travelling companion of those who suffer, who has mercy on him and cares for him.

Suffering is part of the human condition, it is our daily bread; and if Elohim is the God of life, we can certainly also find him at the bottom of our or other people's suffering. Sometimes the night of pain allows us to see the most distant stars, and to feel that the void created by the suffering is "inhabited". The encounter with suffering can make us access the deeper dimensions of our life, when in the nudity of existence we can meet a truer "me" that has been unknown so far. At other times the pain makes people become worse, it takes the light of day away and we can no longer even see the sun at noon. Too many poor people are crushed by suffering that does not make them more human. The first chapters of Genesis tell us that the suffering of Adam was not in God's original plan and that its source is external to Elohim. The Bible knows that the gods that feed on the suffering of man are called idols.

But Elihu cannot use his argument to explain the suffering of Job. Job is righteous and innocent, he was not or is not in any condition of mortal sin from which he should exit by way of suffering. So despite having to recognize the anthropological and spiritual value that suffering can sometimes produce, no humanistic and therefore true reading of the Bible can make God the cause of the suffering of people, let alone the innocent. Which God's actions could be associated with the suffering of children, the destruction of the poor, the cry of the many Jobs in history? And if anyone were to come up with such an idea, they would be constructing inhuman religions and gods that are too small to be up to the best part of us that continues to suffer when faced with human suffering. What religious sense would a world have where the better humans have to be fighting the suffering that God would cause? None. Those who are crucified without resurrection do not save either people or God, and anyone who tries to constrict religions to Good Friday is preventing the flourishing of man and God. Solidarity and fraternity are born and reborn by our capacity to suffer for the suffering of others, our compassion for the pain of every woman and every man. It is this caring God that Job is seeking: a God who is the first to suffer from the pain of the world, the first to take action to reduce it by redeeming the poor and the victims.

Download pdf