Economic soul/1 - From the thinking of Antonio Genovesi in the 18th century, heir to the medieval tradition, to the long eclipse of the 19th century. Until the 20th century

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on January 11, 2026

“An important path to follow is that of a different reading of the history of economic thought, and in particular of the Italian tradition, as is already beginning to be done, reevaluating Genovesi and other civil economists. If we were able to identify an Italian tradition, different from the one that has become official [mainstream], which has its own genealogy, this would be an operation of primary importance.”

Giacomo Becattini, “Human well-being and ‘project’ enterprises,” 2002

There have been periods in European civilization when the love, pain, experiences, and experiments of Christians have generated words of flesh that have then become papal encyclicals, documents, magazines, and books that have universalized and generalized that civil love and pain. We would not have had Rerum Novarum (1891) – or it would have been much poorer and less influential – without the cooperative movement, rural banks, the trade union movement, workers' leagues, mutual aid societies, the Opera dei Congressi (Congress Work)... Of course, the theological ideas of Father Matteo Liberatore and the socio-economic ideas of the young professor Giuseppe Toniolo were also important, but it was first the facts that sifted, discerned, selected, and valued the ideas of theologians, philosophers, economists, and then popes. In Christianity, it is not ideas that validate facts, but the opposite. ‘Reality is superior to the idea’ is not only a principle very dear to Pope Francis, but above all a synthesis of Christianity, of its humanism based on the Word made flesh - the Logos did not enter history by becoming an idea, an ideology or a book, but by becoming a child. Ideas are alive, life-giving and capable of transforming the world only when they are flesh.

Therefore, the impact, quality, and transformative capacity of a Church document depend greatly, almost entirely, on the quality and generative capacity of entrepreneurs, cooperators, politicians, citizens, scholars, and above all, entire Christian communities, who live and experience new things in their individual and collective flesh. The ‘sympathetic’ ink of important Church documents is the blood of witnesses and martyrs. We are all awaiting Pope Leo's first social encyclical, and we are well aware that this document cannot create reality: it can see it, give it wings, amplify it, it can turn some small ‘already’ into ‘not yet’; but once again it will be the reality that the Church and humanity are already experiencing that will give quality and impact to Leo XIV's encyclicals, as was the case with Leo XIII's Rerum Novarum. Without this ‘flesh’ and this life, encyclicals are paper documents that do not improve the economic and social world.

The series of articles we are beginning today is an exploration of the intertwining of economics and Catholicism in contemporary Italy, particularly during that long century that took us from the mid-19th century to the end of the 20th century, passing through socialism, modernism, wars, and fascism with its ‘corporatist’ economic doctrine, which we will also deal with. Economics and the Catholic religion will therefore be the two axes of this reflection. In some articles, economics will prevail, in others religion, but in all there will be dialogue between the two.

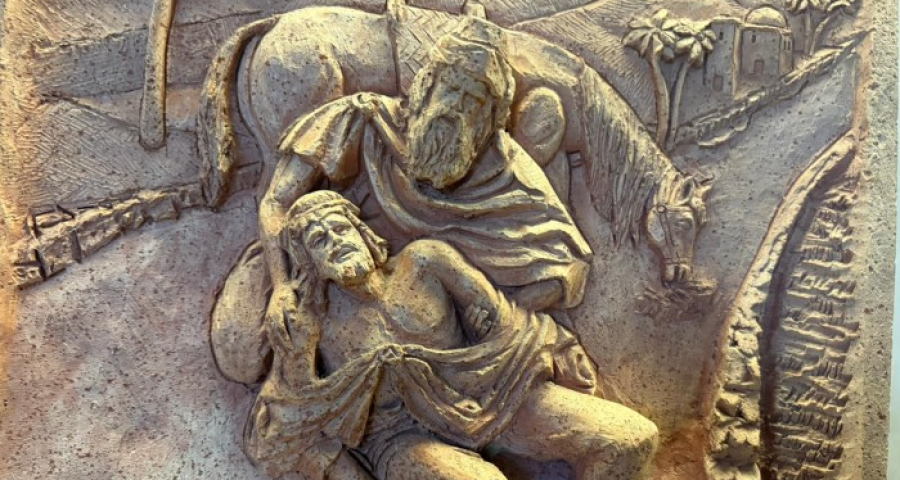

To speak of Italian economic tradition means above all to speak of civil economy, which is the name that economic science took from its origins with Antonio Genovesi in the mid-18th century, when an economic-civil tradition that began in the Middle Ages with monasticism, merchants, the Franciscans and their doctrines on usury, their Monti di Pietà and Monti frumentari came to maturity. With the birth of the unified state, that ancient tradition of Italian (but also European) thought underwent a fracture and then a long eclipse. And that is where we start.

Until the early 19th century, the Italian tradition of civil economy was still alive and respected. Between 1802 and 1816, Pietro Custodi of Milan published the ‘Collezione degli Economisti Classici Italiani’ (Collection of Italian Classical Economists) in fifty volumes, a fundamental work for the dissemination of Italian economic thought in the new universities and among the new politicians. But when, in 1850, on the initiative of Francesco Ferrara, who was the most influential economist of his generation, the Biblioteca dell'Economista (Economist's Library) was created, only one of the 13 volumes (the third) was dedicated to Italian economists. The cultural climate was, in fact, changing rapidly and radically. In his introduction to that third volume, Ferrara has kind words for Genovesi, whom he, not surprisingly, places as the first author of the volume: ‘The oldest chair of economics in Italy, and one of the oldest in Europe, is that of Naples, established in 1754 by Genovesi’. He then provides some biographical notes on Genovesi: "Unpopular with the monks and priests of the schools, whose ignorance served as a dark backdrop to the splendid fame of this innovative priest, who, avoiding Latin as much as possible, relying on arguments that rebelled against the strict forms of syllogism, quoting English and French authors, pronouncing with equally impassive lips the truth of the Bible and the passage of the heretical writer, was nevertheless enthusiastically frequented by an eager youth... This was Genovesi" (Vol. 3, pp. V-VI). Genovesi, also on the explicit recommendation of Intieri, the financier of the chair, taught in Italian (not Latin), an innovative fact that did not escape Ferrara: “According to the custom of the time, Genovesi began the next day to dictate his lessons to the young people; and he himself recounts that it seemed a marvel to hear a professor speaking Italian from his chair for the first time,” and denounced “the fault of the Italians in holding their language in very low esteem” (pp. VII-VIII), a fault that continues and grows today. So much for the fine words about Genovesi and his Economia civile.

Despite his personal esteem for Genovesi, however, Ferrara believed that the true science of economics was now only that of the English and the French. Genovesi and the Italians were merely prehistory, the ancien régime: “The merits of the first foundation of economics belong to the Englishman Smith or the Frenchman Turgot, not to Genovesi” (p. XXXVI). The Italian tradition, in his opinion, had not been able to enter modernity because it was still imprisoned by moral and political concerns. Economics as a science independent of both morality and the ‘prince’ had instead been founded by Adam Smith in his Wealth of Nations (1776): “The ancient Italian school offers nothing that might recommend it to our preference... I will share the sentiment of national self-love, but I will continue to study Smith in order to learn economics” (p. XXXV). And so he concludes coherently: “If the Biblioteca dell'economista had been assigned a less ambitious purpose than it had, perhaps none of the Italian authors now included in this volume would have been included” (p. LXX). This was a very strong and clear thesis, which proved decisive.

Genovesi's non-modernity lay, therefore, in his choice to frame issues in a ‘broad and complex’ manner. His mistake was one of method: he failed to look at wealth from an ‘abstract and absolute point of view, but rather from that of general welfare’ or public happiness. For Ferrara, on the other hand, Smith was the true founder of modern economic science, precisely because he abandoned this ‘broad and complex approach’ to focus solely on economic variables - it is the birth of homo oeconomicus (more in Ferrara than in Smith): ‘Smith's merit lies in having felt the need to abandon ... broad and complex formulas before others did’. And this was ‘an immense step forward’, it was ‘the Cogito of economics’ (p. XL).

For Ferrara, the reference to 18th-century Italian economists was therefore an attempt to ‘cover up the nullity of the present with memories of the past’ (p. LXX). The nullity was obviously that of his present—the mid-19th century was certainly not a time of great theoretical talent for Italian economics—but the temptation to return to a noble past when the present is poor (as ours is) is always present. Therefore, Ferrara's warning is also important for us today, an invitation not to console ourselves by remembering the great fathers in the time of the little grandchildren.

Francesco Ferrara was a staunch liberal economist and a child of the century of Darwin, Marx, and positivism, a colleague, in method, of John S. Mill. For him, ‘true’ economic science could only arise by renouncing the ‘whole’ in order to study the ‘fragment,’ leaving aside ‘public happiness’ to focus on production costs and consumer utility. Ferrara was the bridge that Italian civil economics of the 18th century had to cross to reach the second half of the 19th century. It was a very narrow bridge, almost a needle's eye, which allowed very little of that great classical heritage to pass through, too little for any trace of it to remain.

After this passage, civil economy left academia, but - and here is a key point - it also left the thinking and action of the Catholic world, its economists and sociologists, cooperators, trade unionists, popes, and bishops. In fact, starting with the leader Toniolo, the Catholic tradition that would inspire Rerum Novarum and then Social Doctrine would not reconnect with Genovesi or Civil Economy, which were ignored or considered too modern and distant from the neo-Thomism that would guide many documents. We cannot understand the Social Doctrine of the Church between the 19th and 20th centuries unless we bear in mind that it developed during Pius IX's Non expedit and the modernist controversy of Pius X and his successors until Vatican II. This was a climate of closure to the modern world and its demands for a scientific study of the Bible, not least because these demands came mainly from Protestant countries. Added to this already complex picture was the birth and development of socialism and Marxism, which further complicated dialogue with the past and with the contemporary world, occupying much of the energy of Catholics, probably too much.

The disappearance of Italian civil tradition from the thinking of the Church is one of the reasons for the failure of Catholicism to engage with modernity and for its anti-modernism, which are still a serious problem for the Catholic world and its reflection on the economy and society. Genovesi, who, according to Ferrara, was too little modern because he was fascinated by ‘broad and complex formulas’, became instead too modern and with categories too broad and complex to fit into the Thomism that Leo XIII had placed at the center of the Church's thinking. Along with civil economy, Franciscans, monasticism, Tuscan merchants, pawnshops and grain banks, Bernardino da Feltre and Muratori, together with a serious biblical perspective, were also left out of Catholic social doctrine. All this was shrouded in a dark night that lasted almost two centuries, which we will discuss in these articles. During this long night, some angels slipped in along with many ghosts, which still populate the dreams of the Catholic world. Perhaps it is time to wake up.