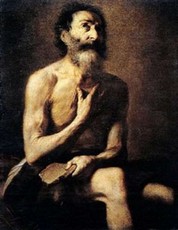

A Man Named Job/4 – He who is righteous can say it out: no son deserves to die

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 05/04/2015

(Fyodor Dostoyevsky, "The Grand Inquisitor", The Brothers Karamazov).

Biblical humanism does not ensure happiness to the righteous. Moses, the greatest prophet of all, dies alone and outside of the promised land. There must be something more real and deeper in the search of happiness of the righteous. We ask a lot more from life, above all the meaning of our unhappiness and that of others. The book of Job is from the side of those who are stubbornly looking for a true sense for the disappointment in the big promises, the misfortune of the innocent, the death of the daughters and sons, the suffering of children.

After the first dialogue with Eliphaz, now it is the second friend to speak: Then Bildad the Shuhite answered and said: “How long will you say these things, and the words of your mouth be a great wind? Does God pervert justice? Or does the Almighty pervert the right? If your children have sinned against him, he has delivered them into the hand of their transgression." (8,1-4). In order not to question the justice of God, Bildad is forced to deny the righteousness of Job and his sons. For his ethics, which is abstract and without humanity, if the children (and Job) were punished it means they had to have sinned. His idea of divine justice and order bring him to condemn and thus betray the other/man. But there are many children who die without any sin, yesterday, today and always. In the French Alps, in Kenya, on the Golgotha. Anywhere. There is no sin that requires the death of a child to be atoned, unless it is the denying of any difference between Elohim and Baal, between YHWH and hungry idols.

The poem of Job is a test of the justness of God, not that of Job (which is revealed to us from the very first lines of the prologue). It is Elohim who must prove that he is really just, despite the pain of the innocent.

To respond to his 'friend', there are two roads opening up in front of Job. The first, which is always the easiest, is to admit that there is no justice in the world: God does not exist or is too far away to master fair judgement of men. The second way is to attempt the unthinkable for his time (and for believers of all times): to question the righteousness of God, asking him reasons for his acts. Job in responding to Bildad crosses through these two extreme possibilities: “I am blameless; I regard not myself; I loathe my life. It is all one; therefore I say, ‘He destroys both the blameless and the wicked. When disaster brings sudden death, he mocks at the calamity of the innocent. The earth is given into the hand of the wicked;" (9,21-24). He doesn't care about his life (and this is pure gratuitousness), but justice in the world; and so Job dares the non-darable, coming to deny the possibility of the existence of any kind of divine justice.

Here Job continues to expand the horizon of the human realm contained in biblical humanism, taking all those in his ark who continue to wonder if there can be a good and just God in a world of inexplicable pain and evil. Job tells us that an unanswered question may be more religious than the answers that are too simple, and that even a 'why' can be prayer.

After Job there is no truer rosary on earth than that consisting of all the desperate questions of 'why' without answers, rising toward a sky that they still want to see as a place that is inhabited and friendly to them.

Job continues to seek a foundation for the earth that should be deeper than chaos and nothingness. But to search for and want a true God beyond the apparent 'banality of good', with the strength of its fragility Job asks God to answer for his actions, he wants a responsible God.

In fact there would be an easier way: taking the shortcut suggested to him by his friends, admitting his guilt. However, for a mysterious loyalty to himself and to life Job does not follow this third way. Job could have admitted to be a sinner (which righteous man is not consciousness of it?), he could have begged the forgiveness and mercy of God, thereby saving the justness/righteousness of God, and also hoping to gain his own personal redemption. But he did not, and he continued to ask for reasons, to keep the dialogue up, to wait for a different face of God. To believe in his own righteousness.

A great difficulty that a righteous person faces during the long and exhausting trials of life is not to lose faith in their own truth and justice. "It was not true that I did it for the good...", "I was acting superior..." "Deep down I am but a bluff..." But when our sins (that are always there) suggest us a reading of our lives that gradually becomes the most convincing one, we lose every engagement with the truth and we get lost, even if for a different and less true desperation we ask forgiveness and implore the mercy of God and others. This giving in is not humility, but only the last great temptation. We can hope to save ourselves from the trials similar to those of Job only if the history of our innocence and righteousness is more convincing to us than the history of our sins and our wickedness. It is fidelity-faith in that something that was very beautiful and “very good” (Gen 1,31), and what we are and we remain despite everything, which can save us in times of great and long trials. It is to this dignity of his (and ours) that Job, too, clings: “Remember that you have made me like clay” (10,9). A faith that also includes the children, the people we love, and the faith that one day may include every human being. Job continued to believe in his innocence so that we, who are less righteous than him, can now continue to believe in ours.

Furthermore, Job cannot believe that his children had deserved death. No child deserves to die. On this earth there is much truth and beauty because mothers and fathers continue to believe, sometimes against all evidence, that their sons and daughters are not guilty. We have been saved so many times and are still only because at least one person kept believing that our beauty and goodness were greater than our mistakes. What a sad place this earth would be without the resurrecting looks of the mothers and fathers?

The extreme loyalty of Job himself pushes him into a most subversive act. He does not want to deny the righteousness of God, but he cannot deny his own truth either. So, from the grip in which he seems crushed, there emerges an unexpected third possibility, an unthought and unthinkable one. Job summons God himself to be judged. His dunghill turns into a courtroom. The accused one is Elohim, his lawyers are Job's friends, the inquisitor is Job: “I loathe my life I will give free utterance to my complaint; I will speak in the bitterness of my soul. I will say to God, Do not condemn me; let me know why you contend against me. Does it seem good to you to oppress, to despise the work of your hands and favour the designs of the wicked?” (10,1-4).

But - one may ask - how is it possible to sue God, to denounce him, if the accused person is also the judge? “For he is not a man, as I am, that I might answer him, that we should come to trial together. There is no[d] arbiter between us, who might lay his hand on us both.” (9,33). In fact there is a judge-arbitrator present throughout the book of Job: the reader who, in the course of the play is called to participate, to express themselves to one or another of the contenders. A reader-arbitrator who is a contemporary of Job would have condemned him, considering his harangue an act of pride and indolence. The defence of Job has developed with history, with the prophets, the gospels, Paul, the martyrs, and then modernity, the lagers, terrorism, the euthanasia of children. Job is more contemporary to us than he was to the man of his own time, and he will be even more so in the centuries to come.

With the 'lawsuit of God' we are then inside a true religious revolution: God must also give an account of his actions if he wants to be the foundation of our justice. He must make himself understood, he must say other words in addition to the many he had already said. If he wants to reach the status of the biblical God of the Covenant and the Promise and free himself from the idolatrous cults, stupid as their fetishes. Therefore the Book of Job, nestled at the heart of the Bible, takes us on a high peak and it invites us to look at the entire Torah, the prophets, and then the New Testament, the women and men of all times from there. It stands as a test of the truth of the books that precede it and those that follow.

There was another time, when a trial took place with God as the accused in it. The roles, however, were reversed. Man was strong, almost omnipotent, the one who questioned and judged. God was fragile, condemned, crucified. It is between these two extreme trials that all justice, injustice and the hopes of the world are inscribed. Job did not and could not know this. But he was probably the first one to celebrate the empty tomb. Only those crucified can understand and desire resurrection. Happy Easter.

Download pdf