Greater than Guilt/9 - Work is never an obstacle to our vocations

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 18/03/2018

Rabbi Bunam once prayed in an inn. Later he said to his disciples, ‘Sometimes you think you can't pray in one place and you look for another. But this is not the righteous way. For the abandoned place will complain to him: »Why did you not want to pray on me? If there was anything that disturbed you, it was a sign that you had the obligation to redeem me«.’

Rabbi Bunam once prayed in an inn. Later he said to his disciples, ‘Sometimes you think you can't pray in one place and you look for another. But this is not the righteous way. For the abandoned place will complain to him: »Why did you not want to pray on me? If there was anything that disturbed you, it was a sign that you had the obligation to redeem me«.’

Martin Buber, Tales of the Hasidim

Saul’s decline intersects with the rise of David, the bright star of the Bible, perhaps the brightest of the Old Testament. He is the biblical character whose heart we know best - a word that, not by chance, appears already in the first account of his vocation ("Humans see only what is visible to the eyes, but the Lord sees into the heart"; 1 Samuel 16:7).

Abraham and Moses are immense figures of the Bible, even more central than David in the history of salvation. We know their undertakings, words, above all their faith, and these are sufficient to make them the pillars of their people and the covenant. We do not know Abraham or Moses’ heart, however, or we know very little about them. Mount Sinai and Moria are places of great dialogues, perhaps the greatest of all, but the biblical text does not tell us what really happened in the soul of Moses and Abraham. It lets us imagine it, and it is for this reason, too, that writers and artists over the centuries have been able to "complete" the intimate stories of these men of God, who were only evoked or whispered in the biblical text.

The Bible opens David’s heart to us; it makes us enter his inner life, emotions, his feelings and tragedies. Thus the narration of his story offers us some of the most exciting and sublime pages of ancient literature, and David becomes a much loved king although more sinful and "smaller" than other biblical characters. David resembles Jeremiah: both are called young, both are seduced in their heart, both are great for their accomplishments and gestures, but loved above all for the pages of their diaries of the soul, for their songs and the intimate psalms of their heart. With David the sound, song and friendship become the word of God, human values and feelings acquire the right of citizenship in the heart of the Bible, which is the great code of our civilization not only and not so much because it speaks to us differently about God, but because it speaks to us differently about men and women, because it speaks to us differently about ourselves, to tell us who we are.

“The Lord said to Samuel, »How long are you going to grieve over Saul? I have rejected him as king over Israel. Fill your horn with oil and get going. I’m sending you to Jesse of Bethlehem because I have found my next king among his sons«” (1 Samuel 16:1). The new word of God for Samuel begins with a reference made to Saul. Samuel cries for Saul who has been repudiated. The text does not tell us why Samuel is crying. We can think, however, that the repudiation of Saul by YHWH caused Samuel pain. He had sought him out and consecrated him; he had kissed him, and then he had participated in the joy at the celebration of his enthronement. Saul's failure was also Samuel's failure, as happens in life when the failure of those we choose for a task becomes our failure, too. Those who lead communities and organisations know that we cannot break away from the failures of the people we have entrusted ourselves to. Even if the objective responsibility for failure is not ours, that pact which created that task and that task is reciprocity embodied. And, as in all pacts, the failure of the other is my failure, too. It is true that Samuel, a judge and a prophet, acted and spoke on YHWH's command. But the honest prophet, when he pronounces the word he has received, becomes personally supportive of the word he says. Always, but especially when things go wrong.

Samuel's weeping for Saul's repudiation, which follows his cries ("Samuel was upset at this, and he prayed to the Lord all night long" 15:11), therefore, repeats the mysterious and wonderful dynamics of the word and prophecy in the Bible to us. Prophecy lives by a double pact of faithfulness: that between God and the prophet and that between the prophet and the word. At the moment when Samuel acts and speaks based on the word he received, a faithfulness-solidarity begins between the prophet and the words he pronounces, which goes as far as the ethical duty to feel pain in his flesh for a word that is not fulfilled for reasons that he cannot control. The prophet is not a machine, he is not an indifferent mediator between God and the world. Instead, he is a living and incarnate channel, and when the word passes through him to reach the earth and become effective, he becomes part of the stories and actions that the word operates, and follows its fate. If Samuel had not cried for a word of YHWH gone wrong he would not be a responsible prophet but simply a false prophet who does not suffer from the failure of the words he has said because they were just vanitas, smoke, fake news. Saul's anointing was born of an authentic word, and it operated as such, it was performative, it changed reality forever. “It will be like you’ve become a completely different person,” (10:6) said Samuel to Saul on the day he anointed him. If that word was real, it was an efficient word. God may change his mind and/or Saul may sin, but it is Samuel's weeping that tells us that words are not like the wind, and that Samuel was an honest prophet. To tell us the immense value of the word and words in the Bible - and in life.

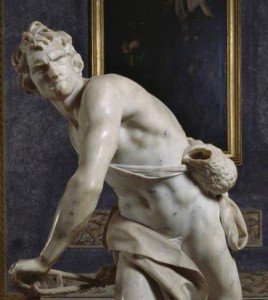

Samuel departs, he goes to Jesse, to Bethlehem: “When they arrived, Samuel looked at Eliab and thought, That must be the Lord’s anointed right in front. But the Lord said to Samuel, »Have no regard for his appearance or stature...«” (16:6-7). Samuel still seems confused, inside a scene that reminds us too closely of Saul's calling while in search of lost donkeys. He is struck by the appearance and stature of Jesse’s eldest son (Eliab), a young man with characteristics similar to those of Saul (handsome and tall). Jesse introduces all of his seven children, but “Samuel said to Jesse, »The Lord hasn’t picked any of these«” (16:10). And here comes the turning point in the narrative: “Then Samuel asked Jesse, »Is that all of your boys?« »There is still the youngest one,« Jesse answered, »but he’s out keeping the sheep.« »Send for him,« Samuel told Jesse” (16:11). The eighth son, the youngest, the missing one, the shepherd boy joins Samuel and the rest of his family: “He was reddish brown, had beautiful eyes, and was good-looking. The Lord said, »That’s the one. Go anoint him.« So Samuel took the horn of oil and anointed him right there in front of his brothers. The Lord’s spirit came over David from that point forward” (16:12-13).

It’s a splendid scene, which was most probably even more elaborated in the first ancient narrations (that are now lost). Merit in the Bible is something radically different from our meritocracy. There are some striking details here taking on a great theological and anthropological value. The narrative structure of the text shows us a dialogue between YHWH and Samuel, where even God needs to see David's face before saying to Samuel: “That’s the one. Go anoint him.” The Bible is certainly a humanism of the word, but it is also a humanism of the gaze and the eyes. From Elohim's first look at Adam when he saw that "it was very good", to the second look exchanged between two humans, finally "eye-to-eye", to that look between Jesus and the rich man: “Jesus looked at him carefully and loved him” (Mk 10:21). David is the youngest among his brothers. His father Jesse had not even invited him to the sacrificial banquet, given his young age which did not allow him to participate in the sacrifices. We are thus entering another great episode, perhaps the greatest of all, of that economy of smallness that permeates the entire Bible, and represents its deepest spirit.

The Covenant, liberation, conquest and protection of the earth, prophecy, live by a vital and fruitful dialogue between strength and weakness, greatness and smallness, law and freedom, institution and charisma, temple and prophecy. They are the weft and warp of salvation history, which only allow us to see the shapes, colours and beauty of humanity's plan together. But at the decisive moments of this story, the Bible tells us that the co-essential nature of these two principles does not go so far as to deny the existence to the primacy that belongs to the oikonomia of smallness. That of Abel, the sterile women and the mothers, Joseph, Amos and Jeremiah, that of David, of Bethlehem, the Beatitudes, Golgotha. The logic of the economy of smallness is born directly from the idea of God, that of the person and relationships contained in the Bible. It tells us that YHWH is a "subtle voice of silence", his temple is an empty temple. He is a voice, he cannot be seen or touched, and he chose the smallest of peoples as an ally. He becomes a child and then lets his own son and our children hang on a cross. But it also tells us that the spiritual life of the person really blooms on the day when they begin to realize that salvation is found in something so small that they have not even "invited to the banquet”: in those failures of yesterday, in those wounds of the soul, in those questions that we have dismissed, in those sins and shortcomings that we do not want to look at. Taking this economy of smallness seriously leads us to look at the world in a different way. To seek the kings of tomorrow among the discarded and the poor of today, to take the young and children very seriously, to find merits where the oikonomia of greatness can only see demerits.

There is one last small detail, so humble that it often remains in the background of the story. As Samuel looks on his brothers, David is “out keeping the sheep". In his family he was the only male working at that time (perhaps with his sisters and mother whom we can imagine taking turns at work with him). He was grazing the flock, like Moses did on Mount Horeb. Work is not an obstacle to our greatest calls, because, simply, the most important and real vocations and theophanies happen while "we are out keeping the sheep". This is a wonderful song about laicity and work. To discover our vocation and thus understand our place in the world, we can do nothing better than work.

download pdf article in pdf (75 KB)