Economic Soul/6 - Catholicism's complex relationship with modernity in the development of the Church's social doctrine

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on February 15, 2026

The relationship between Catholicism, modernity, fascism, economics, and society in recent centuries is a rough and little-explored territory. Every hermeneutic hypothesis is a map, an essential tool for attempting to venture into it, aware that we have in our hands an incomplete and partial geographical map. A map is not a photograph of the forest, nor is it a fraction of that ‘1 to 1’ map of the Empire imagined by the genius of Borges. It is only a humble piece of paper, with many holes and dots connecting areas that are not described because they are unknown, some of which can even lead us to the edge of a precipice - both the writer and the reader. But there are no other good ways, the only one left is the apologetic one of ideological a priori and narrative myths, which is always the most loved by all empires and their nostalgics.

Leo XIII and then Pius XI, dedicating encyclicals to the ‘social question’, were innovators, Leo first and foremost. They were innovators because they said that it was an essential part of the Church's mission to get to the heart of the economy, work, and social and political dynamics. They therefore asked important and good questions of Catholics and everyone else. The answers they offered within the constraints of their time have, however, been overtaken by history, partly because they were born in a climate of fear and defense, which are always bad advisors to any writer on social issues. During times of great fear, both individual and collective, the first path that lies before us is that of returning to familiar and reassuring ground, and this is not the right path.

To continue our journey, let us look at the work of Amintore Fanfani, professor of economic history and economic doctrines during Fascism at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan, oriented in those early years by the ‘medievalist’ program. Father Gemelli saw Fanfani as a star, and when he was still only 25 years old, he entrusted him with the direction of the prestigious Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali (International Journal of Social Sciences). His first and most important works are dedicated to the search for a foundation for capitalism, whose spirit, for Fanfani, is not good but the evil fruit of the decline and betrayal of the authentically Christian spirit that had sustained medieval Christianitas. He thus traces back to the late Middle Ages an economic culture radically different from what would become the capitalist spirit. He found the unspoiled spirit of the economy in that distant land where the modern germ had not yet entered the European organism, infecting it. The early medieval economic spirit was good because it was pre-capitalist, and therefore social, virtuous, communal, ordered by guilds, and protected under the wing of the Church, the theology of Thomas Aquinas, and Scholasticism. This Christian order of the first communes and the first merchants, so dear to Dante, would later be distorted by the “new people and sudden gains” (If XVI,73) that “produce and spread the accursed flower” (If IX,130). A turning point that began very early, in the 14th century, with the development of Humanism. The evil breeze of modern man and therefore of capitalism slipped into those cracks in the wall of the sacred medieval order. A failure that occurred well before the Reformation of Luther and Calvin. Fanfani could not agree with the theory of the great sociologist Max Weber, who a few years earlier in his The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism had linked the birth of capitalism to the Calvinist spirit. For Fanfani, the capitalist spirit is neither Christian nor Catholic; it is a betrayal of both. Instead, it arose as a side effect of the moral and religious decadence of modern man, and the Reformation did nothing more than continue that misguided and older revolution (let us not forget that that period of Catholicism was also anti-Protestant). Fanfani's interest in the origins of capitalism can already be found in his thesis at the Catholic University: “The enemy of capitalism cannot be a system in which economic reason is the last resort; the enemy of capitalism can only be a system that places other criteria above economic ones” (A. Fanfani, Effetti economici dello scisma inglese, 1929-30). The pre-capitalist age, therefore, was “the era in which well-defined social institutions, such as the Church, the State, and the Guild, became guardians of an economic order not based on criteria of economic and individual utility. A typical institution of the era is the guild” (Cattolicesimo e protestantesimo nella formazione storica del capitalismo, 1934, p. 34). Fanfani therefore categorically denies that “Catholicism, as a body of doctrine, favored the emergence of the capitalist conception and thus the advent of capitalism” (p. 98). He then asks: “When and where did capitalism arise? In Protestant countries, after Luther's rebellion?” (p. 111). His answer is clearly no. The birth of the capitalist spirit predates this and is instead found in “circumstances that led individuals to act differently from how most of their contemporaries acted or how everyone should have acted” (p. 118). In particular, the development of long-distance trade played an important role. In foreign countries, far from the eyes of the community, “there is less incentive for merchants to act fairly” (pp. 119-122).

All this was therefore fully consistent with Toniolo's project, with Gemelli, Thomism, Leo XIII, and Pius XI and their cultural project of restoring the medieval order, its spirit, and its guilds, all essential elements of paradise lost. The Christian social project was therefore supposed to be a way of overcoming capitalism, but instead of moving forward, the aim was to overcome it by going backwards. According to Fanfani, the economic order was based on voluntarism (strong state intervention), thus putting an end to naturalism, i.e., liberalism (Fanfani, Storia delle dottrine economiche, 1942). In this vision, Fanfani considers Rerum Novarum a manifesto of voluntarism (“Rerum Novarum, volontarismo e naturalismo economico,” Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali, 1941).

It is not surprising, then, that the young Fanfani enthusiastically adhered for many years to fascist corporatism, which he saw as the apotheosis of voluntarism and the overcoming of capitalism, a corporatism that Fanfani saw as a development of Christian corporatism: 'Corporatism has denied the essence of capitalism... If there is a country where capitalism is coming to an end and a new system is advancing, that country is Italy. I consider the corporations and all corporate legislation to be profoundly innovative" (Declino del capitalismo e significato del corporativismo, 1934). He also collaborated with the School of Fascist Mysticism (L. Pomante, 2024), created because, in the words of its founder, “fascism has its own ‘mysticism’ in that it has a set of moral, social, and political postulates, categorical and dogmatic, which alone can save humanity in crisis” (N. Giani, 1930). On February 27, 1937, Cardinal A. I. Schuster of Milan visited and gave a sermon at that school, while the Catholic newspaper L'avvenire d'Italia (a predecessor of our newspaper) openly opposed this new ‘mysticism’ (April 9, 1930).

What particularly fascinated those Catholics was the organic and hierarchical vision of fascist society, because it was similar to that of medieval Christianity: “Fascist corporatism has returned to the idea of an organic constitution of society” (A. Fanfani, Il problema corporativo nella sua evoluzione storica, 1942). It has returned... returning, looking back to find the dreamt-of ‘third way’: ‘Corporations were a perfectly Italian form of association, and we owe many of the magnificent treasures that are the glory and splendor of Italy to our old corporations’ (Mussolini, ‘Speech to foreign journalists’, November 1923).

In his lectures at the Fascist Colonial Institute (1936-37), Fanfani interpreted fascism in messianic terms as the return of the empire, even more explicitly in an article in his magazine: 'It took our people only fourteen years to cover the intermediate stages on the road to empire that others took centuries to cover: political pacification, reconciliation with the Church, Roman Catholic and fascist education of the youth: these are the achievements that strengthened our will and paved the way for victory. We were among the last to establish political unity. And the last, alone, will become the first. This is confirmed by the reappearance of Roman virtue on earth, corroborated by the consecration of Christianity“ (”Da soli!" [Alone!], Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali, 1936).

The fascist regime collapsed. The corporative institutions met the same fate. But the corporative mentality, with its search for a middle ground and restoration between capitalism and socialism characterized by a strong state presence, did not disappear after 1945, partly because it existed well before 1922. Traces of it can be found in republican Italy, as we shall see. Just as the Church did not overcome its nostalgia for the old regime and the temptation to look back.

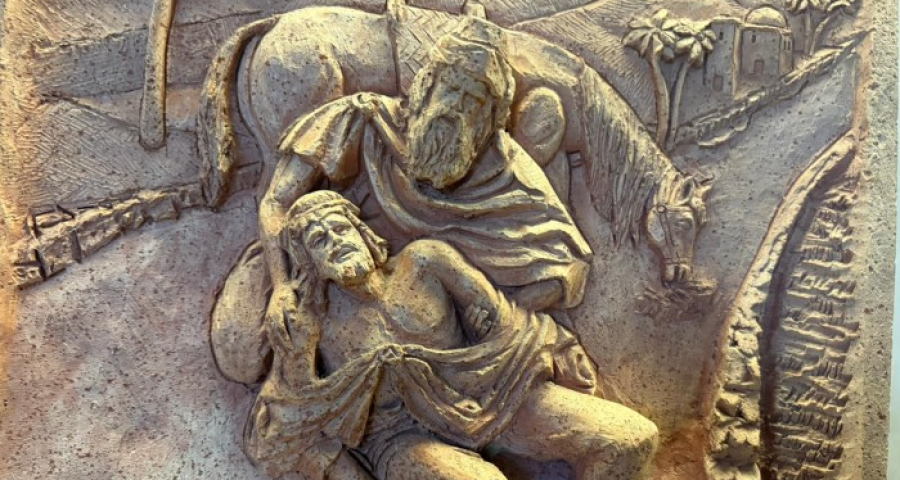

We know from the Bible that when the people imagine a way back, if they actually do so, they end up crossing the sea on the wrong side, where the Nile, bricks, and pharaohs await them. Pope Prevost chose the name Leo to reiterate that even today the social question is central to the Church. And this is a very important signal. It is to be hoped—and there are reasons to do so—that this time it will not be fear of ‘new things’ that sets the tone and words of the new encyclicals. There is an infinite need for a generous and kind view of what humanity is experiencing, including its contradictions and risks. The promised land, if it exists, can only be found within our time, on its horizon.